|

|

|

Theory and Critical Thinking About Art

We live in a world where imagery and visual sensations demand our attention at every turn. Drive down the street, for example, and you will be bombarded with street signs telling you to go this way or that, don’t turn here, okay, you must yield, go this way only if “the coast is clear.” Flashing lights say, STOP, CAUTION, GO. In addition, storefronts scream their wares with big, bright, colorful signs, all hoping to get the passerby’s attention. Most of this visual noise slips by us and into the subconscious.

This has made me think about art, my art, and what place my art has in the viewer’s mind. Like the artists whom I recognize and discuss below, I too want to be recognized. So art must have a venue—it must be seen. I think that artists interpolate their experiences with what other artists have done before them to produce an expression that is cumulative.

I believe Roy Lichtenstein got his ideas from the ink press process of dots per inch and comic books. Perhaps he was even influenced by Georges Seurat and Seurat’s pointillistic style of painting. This process of printing relies on dots; there are a certain number of dots in every inch. If the printing process was for newspaper, there were fewer dots, making the dots very pronounced, the same way that Lichtenstein’s work appears. Similarly, pointillism paintings are filled with small dot like brush dabs. Although pointillism has some characteristics similar to those of Lichtenstein’s work, the time period in which he made this work coincides with the newspaper printing idea. I cannot compare myself to either of these painters but include them in this essay as an example of how we as artists are affected by things in our world.

I have been studying different artists, looking at their work, and assessing where my work compares with theirs ever since I became interested in the arts over 30 years ago. As I studied different artists that came before me or worked right next to me, I wondered why they made the art they made. While at RIT, I studied my fellow students’ work and questioned their reasoning behind why they chose the image they had made. I asked, “What was it about that moment or exposure that appealed to them?” Later on in my career as a professional photographer I found a balance between art and the straightforward commercial work by experimenting with technique and creative expression. I used to think that real artists created from some mysterious place within themselves. I now know that no one is really original and we all copy from each other in some way. None of us is original; we are all imitations in one way or another. My students think that imitating is like cheating. I tell them that imitation is the greatest form of flattery and if you see something that someone else has created and if it appeals to you in some way, that’s okay. I encourage them to build out from that place of interest, to search and to find what it is about the work that appeals to them.

My work can be derived from any mixture of possibilities. Inspiration may come from another artist, whether that influence is a creative expression or an artist technique, a life experience that I have had, or even the subtlest things that happen in life, like a facial expression. My artistic process and in turn my art practice are a side effect from everything I see and experience, good and bad.

My record-keeping process or my digital image captures can be seen as my purest form of artistic expression. The most important moment in my process is when I find a moment in time to record. I sense, I point, I shoot. I don’t have an intellectual reason for taking images when I do. I simply follow something inside me that prevails. It feels mindless and intuitive. I love that place where I am free to express what I am. After the image is recorded it evolves with thought-out execution, sometimes in the darkroom and sometimes in Photoshop. I find meaning in the work at this point.

Joseph Mallord William Turner’s paintings appeal to me on an intuitive level in the same way as some of the cloud images that I have taken (see below). There is something mystical, unclear, or abstract about his paintings. I like that delicate, subtle sensibility in art and in people. He had the ability to see beyond the material reality in a scene and to paint what he felt. He looked at nature with a new vision and painted the elements of air, water, and fire, transforming them into a luminescent glow that is highly emotionally charged, transcendental, and ethereal yet grounded. One might say his paintings show a part of the light spectrum unknown to human eyes. His loose painting style of blending paints leaves me with a feeling of mystic questioning. His work reaches deep into my own imagination and interest in the spiritual side of life, and for that reason he is one of my favorite painters. His conversion from romantic realism to abstract realism influenced the Impressionists, whose work I am also attracted to. To see more of my images in this series click here.

Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and Wassily Kandinsky all leave me with a similar impression although each person’s work is very different. I like the Impressionists because of their abstract traits. They make me feel something more than they make me seek understanding. I also like Jackson Pollock’s work because of the nonfigurative qualities in his paintings. His loose, free-flowing dips of paint have a rhythmic sense about them that is held together the same way I frame an image including this or that. Abstract art is contrary to what I do as a technician. I do it for the same sensation that I get when sitting in front of a fire and watching it for hours. Maybe it goes deeper than words can describe. I go to the opera and I don’t understand the words that I hear but I like it because of pure beauty and sound. Music does not need to be understood on an intellectual basis in order to be understood in the heart.

Kandinsky believed that color was fundamental in its power to affect the human soul. He saw color as the keyboard, the eyes as hammers, and the soul as the piano with many strings. He saw the artist as the hand that played the piano, touching different keys to cause vibrations in the soul. He saw color and form as spiritual symbols. He thought colors could evoke different emotions in the same way that different melodies and sounds do. A non-objective painter, he believed art should be free from its traditional bonds of material reality. He connected representational art with materialism and abstract art with spirituality. Kandinsky studied under a theosophist, from whom he developed his ideas about God, the world, and mystical insight.

In Kandinsky’s painting Improvisation (1914), there are rhythm and tone. The shapes are open; line and color function separately from each other. If a painting could sing, we might be hearing Ella Fitzgerald singing scat with Louis Armstrong loosely playing the horn. Kandinsky’s paintings are abstract yet grounded. They are visually compelling and convey something beyond our material reality. I ask, “What is spirituality?” The answer to that question can vary from person to person. In my opinion, the answer is an unseen world that floats around us and sometimes brushes past us with a force and sometimes a physically recognizable movement. Religion, with its bishops, popes, and men we are directed to respect, is a man-made entity created to control the people. That is a travesty to humanity. Spirituality is something we all have the potential to touch, to take in. There are two worlds, spiritualism and our flesh reality. They exist together and blend into each other seamlessly. Finding balance between these is the construct of existing for me.

Something is happening in Kandinsky’s work that is deeply moving, not just loose, abstract brush strokes and intellectual rhetoric. Kandinsky believed that having recognizable objects in his paintings would actually detract from his work. Sometimes it is necessary, but mostly I don’t include people in my images.

I agree with Kandinsky that art is a spiritual expression of the soul. Like Kandinsky, I do not wish to add obvious material objects to my work. I want my work to be read and understood with the heart and not the mind. The mind gets in the way with its preconceived ideas and preset values.

After reading an article on Kandinsky in ARTnews, I made some new observations about his work that I had overlooked in the past. The article discussed Kandinsky’s Painting with White Border, subtitled Moscow and created in 1913 (see below). The article stated that motifs in the painting were difficult to recognize and dislocated in space. The objects Kandinsky painted were based on shapes that he had included in previous paintings but were less recognizable in this painting. Barnett says, “We can trace the evolution of certain motifs in studies as they become less recognizable and as their positions in space become dislocated.”

The painting is a symbolic representation of Saint George and the Dragon. The three parallel lines curved at the top and placed near the center top of the painting represent the backs of three horses in the Russian troika. Kandinsky included jagged lines indicating the back of the dragon as well as mountains, snakes, and claws, all revealing symbolic representations of the patron saint of Russia, Saint George, the dragon, and the landscape. I never stopped to look at Kandinsky’s work for its translation. I simply enjoyed the movement and flow in his work and made a connection to his music due to the fluidity found in them. I get the feeling that he painted the piece vertically and made the decision to show it horizontally to increase its abstract quality. I intuitively turned the magazine to a vertical position seeking a comfortable resting place (see below). As I read on in the article, Barnett says, “He first conceived the painting as a vertical. … I think it holds up better as a vertical for aesthetic reasons and not representative reasons.”

Kandinsky, Painting with White Border, 1913

The white border is most recognizable in this painting, and therefore Kandinsky named the image by the dominant grounding border. The border does not surround the whole image, but rather it weights the entire painting toward the bottom right side. I looked at this painting for some time before I saw the border separate from the saturated colors in the rest of the image. As I studied the piece, I found that

the border gave the painting depth, like a cloud was hovering over the top of the painting.

This concept strikes a chord in my own work as one of the tools I use to add dimension and movement in an image. This abstract painting needs the white border, which is actually off white with touches of gray, to help ground the image. Kandinsky’s other paintings have consistent bodies of color, which help us viewers place boundaries on our visual understanding. As a rule, I love Kandinsky’s work, but in this case I am having difficulty entering into an understanding due to the lack of framing and boundaries. This provoked me to look with a more critical eye at other paintings Kandinsky made.

Composition VIII |

Composition V |

My work is not as abstract as the paintings that Kandinsky created, perhaps because I am starting from photographs as the source and then working in deeper meanings. I do think that both Kandinsky and I are using subtle ways of communicating deeper meanings, and his ways and mine are both spiritual. Click here to see the work that I have created with spirituality in mind.

Josh Simpson is a glass artist who incorporates very earthy objects into his glass works. This abstract quality makes me question its place in reality. Several of my images that deal with the spiritual have this quality because there is a sense of questioning in them. No one knows for sure what is beyond us when we die. It is all speculation, hope, and uncertainty. Maybe other people don’t care about what happens to them when they die, but I need to have a sense and hope for something more. Otherwise I would see this life as a waste, like a hamster on a wheel. I need to believe in something more in order to keep going. I can’t just live in a self-severing way with no purpose. Having purpose means something to me. I am trying to show hope in my images. I hope that the spiritual work that I am doing is not completely self-serving and functions to enlighten and give hope to more people than myself.

I am also fascinated by the work of photographers who shoot aerial images like Yann Arthus-Bertrand, Jim Wark, and Bernhard Edmaier. All of these photographers capture the essence of floating above the earth, which in my mind helps me to describe the out-of-body experience and spiritual message that I show in my work. I was first drawn to these images while traveling in London and seeing them at the National Gallery. I like the idea of floating above, and I like to fly. It may have something to do with needing to let go, but that would be an assumption and speculative. I shot the image below while flying over the desert in western Utah. Click here to see some of the landscape images that I have taken.

I am drawn to nonrepresentational scenes and objects. My own images may include close-ups of anything that makes the end product image appear abstract. For example, a close-up of a rotting piece of wood may look like something from the universe. I am drawn to its textures and depths. The image below could be a landscape shot from above, but in reality it is a close-up of a piece of wood. Again the idea of something that is illusive appeals to me.

Using a small digital camera, I felt the freedom that I knew when I first started taking photographs. I was free of the technical thought processes that have driven much of my work to date. I had begun to realize that art was an interpretation of a scene and not a technical exercise. This was enlightening and liberating to me. Movement and time exposures all hold value in the same way that Claude Monet’s paintings have meaning. A blurred image may not only be acceptable; the blur can be communicative. To see more of the images in this series click here.

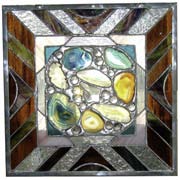

Another artist whose work I like is Piet Mondrian, probably because of his strong linear sense and balance. I think my furniture and craft designs have this same feeling. I guess I am drawn to strong linear lines because they are ordered and not chaotic. Looking at this now I see a direct contradiction to my interests in abstract art. I have an innate sense of balance when I am framing an image in the viewfinder or LCD of my cameras. In some ways I see his paintings called compositions as a grid system of a city from a vantage point of floating above. In this way there is a visual connection to my work. Below is an eighteen-inch-square stained glass piece I constructed that has a similar linear feel and balance. Click here to see my craft work.

Similarly, Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural style and the Prairie school of architecture have this basic grid feeling to them. The furniture that I design and build as well as the craft pieces I build, including the lamp below, have a basic grid system. Click here to see my furniture designs.

The blending and mixing of images that Jerry Uelsmann used in the darkroom with black and white photography helped me to translate my own digital images using Photoshop layers and masks. This is a technical exercise and experimental

process. Actually, most of my art practice is about technical experimentation and what comes from that.

I thought about adding different dimensions to my images after I saw Friedlander’s work. Although I think he was self-absorbed for shooting tons of image reflections that included his own figure, his work made me think about adding additional information to a two-dimensional piece. I attempt to merge dimensions in my spiritual image series by using reflections. The image should give enough information to pull the viewer between the two planes but not be so convoluted that the viewer cannot enter into the image. In other words, there should be distinct objects, subjects, and bits of information on each plane that the viewer can easily read. Friedlander shot images from inside homes, including the home space interior and including outside information seen through a window. This type of image pulls the viewer into two different spaces, yet it is all contained in the same two-dimensional plane.

Last, I would like to share some thoughts and observations on the photographer Diane Arbus. ………………."a thing is not seen because it is visible, but conversely, visible because it is seen………." (Diane Arbus)

Simply put, a moment in time is seen because it has been captured in a photograph. Split seconds, glimpses into bits of time and place, tell a lifelong story. Arbus wanted to hold the past in suspension for the future to see.

She photographed the common things that we pass by every day without notice. I think she was fascinated by people and wanted to take them all in, holding them close to her with her camera.

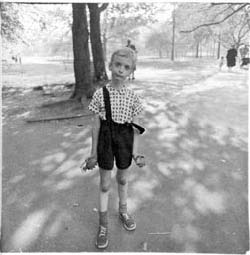

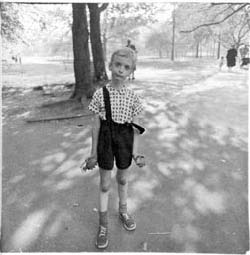

She used a 2 and 1/4 Rolleiflex camera. I have used the same camera to shoot many of the carnival images included in my carnival book, Behind the Colored Lights. She graduated to a Nikon, as did I. She was also a commercial photographer but far more successful as an artist who saw meaning behind a blurry, grainy, or oddly framed image. She sees the image in her camera’s eyepiece and shoots full frame, as do I. She was attracted to Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Mathew Brady, and Eugene Atget, all photographers who shot everyday scenes with telling clarity. They were the documentary photographers of their day. Looking at her images makes me think about all of the images that I have discarded as recorded useless bits of time. She shot the image below in Central Park in 1962. It was one of twelve images she pulled from her contact sheet. I always had the impression either that this image was staged or that she caught the child playing with a toy hand-grenade. The Vietnam War was in full swing. After seeing the rest of the images on the contact sheet, I can see that the child was playing and acting for her while she shot the images, twelve shots on a roll of 120 film.

Arbus

Arbus photographed her dead grandmother and her father as he was dying. She wanted to hold moments of time that deeply touched her. I photographed my mother when she had her larynx and esophagus removed. She smiled back at me despite her face which was two times its normal size from the anesthetic. I also and more recently photographed a good friend as he lay in his death bed. He smiled at me while he held a new gun that he had purchased earlier. This is part of a new series that I call Rural America.

Arbus often shot using ambient light. I think she would have always shot that way except for the slow and grainy films that held her back. Those grainy films add a gritty real-life sensibility to her work.

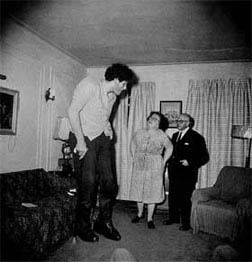

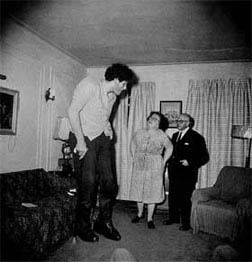

She was drawn to the unusual, photographing all types of people including transvestites, midgets, nudists, circus people, carneys, and the tallest living man. I knew about Eddie Carmel, the tallest living man, from my research for the carnival book. I felt a connection to Arbus’s work because of her subjects. Click here to see my carnival images.

There is great debate on the topic of personal rights when taking someone’s photograph, which is different from the staged portrait that is planned. I think permission or acceptance for frontal images is necessary or it feels like I am stealing something from the subject, which gives me a confrontational feeling, like I was staring. For the most part and depending on the person’s size in the image, they are aware that I am taking the photograph. When it is needed, I get a model release. But in documentary work and artwork, which are not considered advertising, no model release is required. This work falls into the public and photojournalism arena.

Arbus

Many of Arbus’s images look like shots that she has stolen from her subjects. Without their permission, she snaps and runs. I think her camera gave her a presence and a confidence and that at times she hid behind it. Her images have a sad and depressed sensibility about them. After reading things that she wrote, I can see that she was a very complex as well as depressed person. She killed herself when she was only forty-eight years old. I think depression makes you look at life always seeking truth.

I have discussed many artists and styles of art, but I have no particular attachment to any of them. I appreciate each artist for different reasons. I am only influenced, not made a follower by the work. A fully integrated artist should be influenced by everything that is in the artist’s life, not just by a small subculture.

|